What’s On the Other Guy’s Mind? Loss Aversion

Richard Thaler recently won the Nobel Prize in economics. I first came upon Thaler when reading the introduction to Michael Lewis’ The Undoing Project (2017). Thaler and his colleague at the University of Chicago, Cass Sunstein, had written that all of the acclaim for Lewis’ Moneyball1 (2003) could rightfully be traced to two psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Richard Tversky who had been researching and writing about the irrationality of human decision making for years.

Richard Thaler recently won the Nobel Prize in economics. I first came upon Thaler when reading the introduction to Michael Lewis’ The Undoing Project (2017). Thaler and his colleague at the University of Chicago, Cass Sunstein, had written that all of the acclaim for Lewis’ Moneyball1 (2003) could rightfully be traced to two psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Richard Tversky who had been researching and writing about the irrationality of human decision making for years.

Lewis modestly confesses that, until the challenge by Thaler and Sunstein, he had never heard of Kahneman and Tversky. With The Undoing Project, he more than makes up for that.

If I were to recommend one book, though, for readers interested in understanding how we humans make decisions in business settings, it would be Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow (2011) https://www.tildensst.com/2016/12/28/toward-evidence-based-selling/

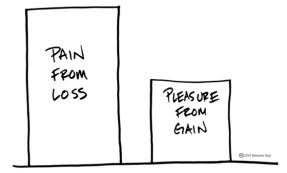

But for the purpose of this post, I thought I would take one key contribution by Kahneman and Tversky, further developed by Thaler, and consider its business implications: Loss Aversion. In its simplest form, loss aversion is a human emotion. As Kahneman puts it, we experience more pain when we lose something than pleasure when we gain it. Loss aversion can be seen in all forms of human endeavor. Those who stand to lose will fight to protect their losses much harder than those who will gain. At its most primal level, this dynamic can be seen when a territory is attacked. The defenders always fight harder. This is true for animals too.

We saw loss aversion both when the Affordable Care Act was proposed in 2010 as well as when its repeal was considered in 2017. Those who perceived they would lose something fought hardest by protesting at town halls hosted by legislators, both Democrats when the ACA was proposed (2010) and for Republicans when the ACA was up for repeal (2017).

Once you are aware of it, you can see loss aversion at play all around us. We can also feel it ourselves. It is an emotion and emotions, not just reason, drive our decisions. The pain of losing in the stock market outweighs the pleasure of winning. I feel that emotion when the pain of a market loss outweighs the joy of a win, even when the percentages are the same.

One clear business take-away, and pardon the pun, is that those who perceive that something is being taken away will fight harder to keep it than those who stand to gain something. This will be true all the way from the important like compensation plans to the mundane like company parking assignments.

Since the title of this blog is Dr. Tilden’s Sales Prescription, let’s consider how the emotion of loss aversion can be applied to selling. One of the fascinating aspects of selling, and its first cousin negotiation, is that while we know what we are thinking, we wonder what is going on in the other party’s head.

Thanks to the findings of Kahneman and Tversky, we know that Loss Aversion will be operating. Thus, when we are proposing solutions that offer gains, we need to understand that the party we are looking to persuade will also be weighing the consequences of any losses. Indeed, they will be weighing potential losses more heavily than the gains most sellers focus on. For example, when our firm sells corporate training we emphasize skill development that will help the client meet strategic objectives. We also need to take into account what the perceived losses might be. Will the training:

Justify taking time away from other responsibilities?

Be perceived as a waste of time?

Be relevant to real life tasks and challenges?

Be customized to our firm or be generic off the shelf stuff?

Provide skills that stick or be quickly forgotten?

Help participants develop personally as well as professionally?

Be fun or boring?

Be something people will thank us for or complain about

In summary, when looking to persuade in settings like selling or negotiation, don’t restrict yourself to the benefits to be gained by your solution. Recognize that the aversion to what may be lost will weigh more heavily in the client’s mind.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

1 Moneyball is the story of how the relatively poor Oakland Athletics out performed far wealthier baseball teams by emphasizing data analysis over old school baseball scouting. Concepts from Moneyball were eventually applied to fields as diverse as banking, education, farming, government, and political campaigns. Moneyball became a movie in 20011 starring Brad Pitt.

One reason why the NRA is so strong

Lou – Good point. Even though most Americans favor reasonable gun safety laws, the NRA succeeds in using principles of “Loss Aversion” to block gun safety. Arnie